My First Lines of Code

At the age of 11 in 2003, I wrote my first line of code. I was a Game Master for a DragonBall Z MMORPG on byond.com. Other than creating a cool-looking pixel art item, I don’t really remember the language or any other details.

At the age of 14 in 2007, I had to take a programming course as part of my high school’s Math and Computer Science (MaCS) curriculum. We used a language called Turing, which is likely unknown to many.

At the age of 16 in 2009, I took the Advanced Placement (AP) Computer Science course after spending a full year learning Java in school.

From there, I wrote code in a variety of languages spanning academic and professional settings: Prolog, JavaScript, Objective-C, C++, Erlang, Elixir, Swift, Python, Go, and probably a few others that don’t immediately come to mind. This spanned roles including iOS development at ModiFace, Android at Google, full stack at Twitter, backend ML infrastructure at Magic Leap, AI eval at Waymo, and blockchain R&D at Pocket Network.

It’s been about six months since I manually wrote a full line of code from scratch, and it’s amazing to realize I may never write code by hand again.

If I don’t have an internet connection and access to frontier models, I’d rather be writing, brainstorming, relaxing, or doing almost anything else.

Some people struggle with this transition. Personally, I don’t find it bittersweet. We can finally focus on what matters: product and engineering.

Table of Contents

- How I code going into 2026

- Orchestrating Agent Personalities

- My AI Tech Stack

- Reviewing Code

- Modes of Operation

- AI Driven Software Engineering

- Use TODOs to Move Fast TODO Everything

- Make everything with Makefiles

- Skills Feedback Loop

- Documentation

- How will teams change?

- A handful of random pro tips

- My favorite blogs

- Closing Thoughts

- Personal Followups

How I code going into 2026

I wanted to capture how I do software engineering going into 2026. Partly to share my workflow with others, and partly to have something to reflect on in the future.

This is not a “tools list” post. This is the actual day-to-day: how I plan work, delegate to agents, review what matters, and keep projects moving without writing code by hand.

Prior to our pivot at Grove in October 2025, I had five senior engineers on my team. They are all engineers I would hire again given the opportunity, but we had to make some tough cost and direction tradeoffs as a company. It’s worth mentioning that I and the rest of the C-suite are hands-on across the entire stack.

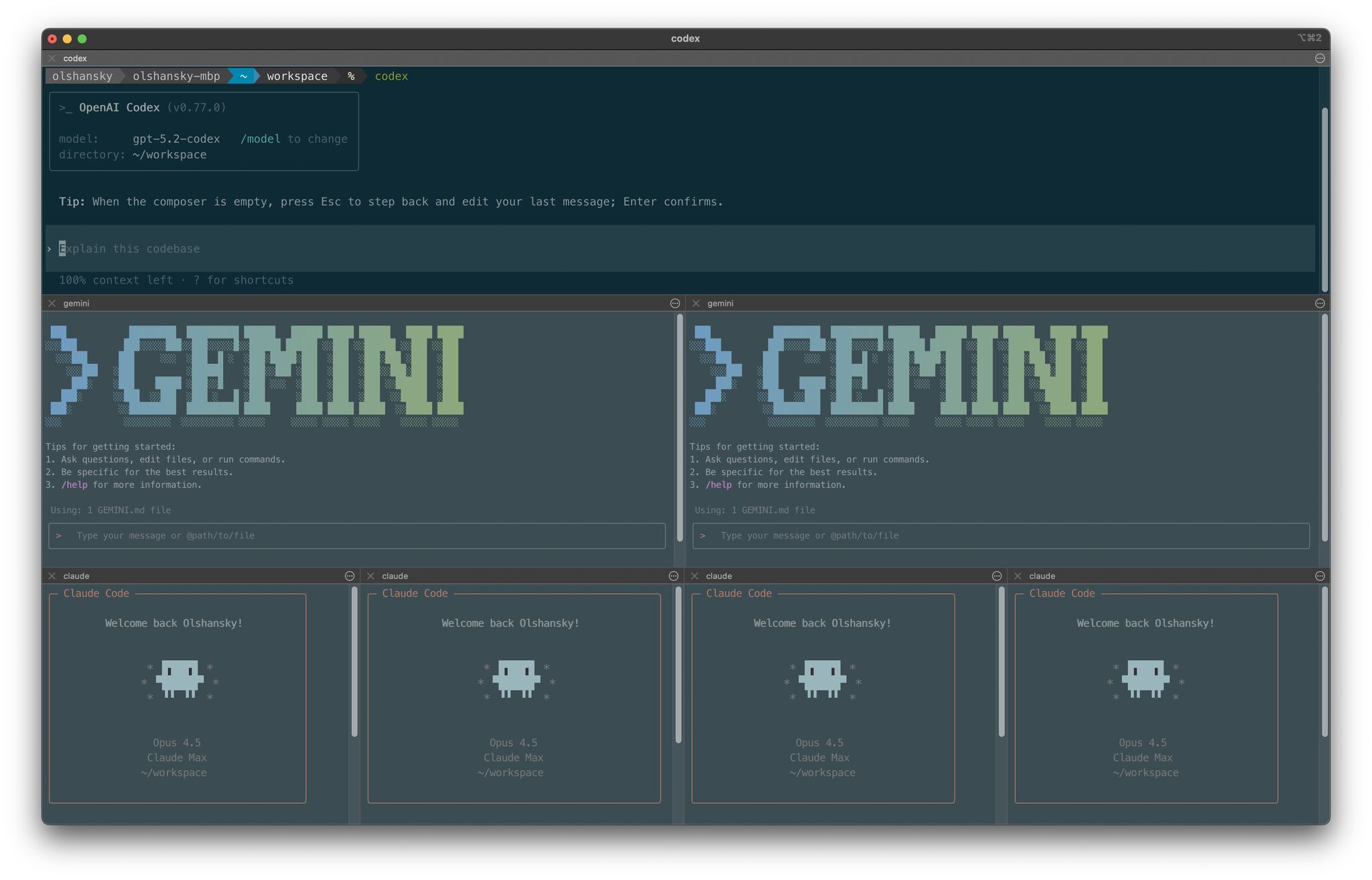

Today, the organization that reports to me looks like this pyramid of agents:

I’ll dive into tips and patterns below. In practice, four Claudes, two Geminis, and one Codex via the CLI capture the majority of how I operate day to day.

I no longer write any code by hand from scratch, at all.

Orchestrating Agent Personalities

Managing agents isn’t just about specifying direction or building automation. It’s about orchestration.

In a symphony, the conductor makes the decisions, but the musicians do the work. No matter how skilled the musicians are, they still need someone to set the rhythm.

I do not believe this part will ever be automated away. It’s the irreplaceable piece people now refer to as taste.

A big part of orchestrating agents is understanding their strengths, weaknesses, and personalities. It’s no different from learning how to work with a team of people, except agents don’t get tired and aren’t encumbered by emotion.

I’ve also noticed that the “shape” and personality of each agent reflects the organization that built it.

Codex (OpenAI): The manager, director, or VP type. Great for planning, scaffolding, and setting direction. In tech firms, this maps to L8+.

Gemini (Google): The architect or principal engineer type. Great at solving hard problems, from AI implementation to low-level optimizations. Strong at design docs, complex bugs, identifying security vulnerabilities, and laying out how code should be refactored. Usually L6 or L7.

Claude (Anthropic): The day-to-day builder. This is the army of developers that ships most of the work across the stack, from scripts and integrations to implementing APIs and UI. Usually L4 or L5.

Some people have asked me how I split and assign tasks from Codex -> Gemini -> Claude. Right now, I don’t have a formal process. I do it manually, and I’m intentionally avoiding over-engineering this part.

A gap I haven’t been able to close yet is letting agents reliably kick off other agents, but I’m confident that’s coming.

Side note: I’d rank the CLI UX from best to worst as Gemini -> Claude -> Codex. This might be the only time Google is superior on product, and it’s because the target customer is a developer.

My AI Tech Stack

- CLI: iTerm2 with over a decade of configs, powered by the Codex CLI, Gemini CLI, and Claude Code.

- Desktop Apps: ChatGPT as my daily partner, Google Gemini for images.

- GitHub: When I review code, I prefer to review it on GitHub. Beyond code review, GitHub is a suite we take for granted: Issues, Pull Requests, Code Reviews, Discussions, Gists, Actions, Permissions, Secrets, CLI, etc.

- IDE: I was a big fan of Windsurf, but switched to Antigravity. It seems the acquisition of the founding team by Google brought parity to the IDE.

Reviewing Code

One of the topics I’m curious to see how it evolves is code review. I’ve seen a lot of companies working on it, but I haven’t invested the time experimenting with those tools yet.

When I was 19 years old, my manager, Ryan Perry, told me:

“You’re going to spend a lot more time reading code than writing code.”

That became obvious when I moved into engineering leadership, but I didn’t anticipate the turn it would take.

For solo projects, I don’t review code unless there’s a serious issue and the agents are stuck in a doom loop.

For shared codebases, it depends on how critical the business logic is and how mature the codebase is. The more critical the logic and the more mature the codebase, the more time I spend reviewing diffs on GitHub line by line. Even when I see changes that need to be made, I ask the agent to do them rather than fixing them myself. I’ve been spending less and less time in the IDE unless I’m updating documentation.

The closer the work is to critical code paths, like updating database rows related to payments, the more I review it.

If the code is related to fast-moving frontend changes, I often don’t review it at all. Instead, I ask another agent to sanity-check that it’s idiomatic, clean, and good enough.

There’s a common saying:

“You are the average of the five people you spend the most time with.”

Extending this to agents:

“Your codebase is the average of the five most influential contributions to it.”

Very simply, agents behave exactly as carefully as you teach them to. Patterns across docs, tools, interfaces, testing discipline, error handling, and “what good looks like” all show up downstream in the code they generate.

The humans prompting agents today determine how future humans prompting agents will behave. Don’t be lazy.

Modes of Operation

There’s never a simple answer to “how do you operate” or “how do you split your time.”

It depends on the state of the team, the product, customer needs, and external market conditions. Sometimes you wear one hat for an entire week. Other times you juggle multiple hats at once.

When it comes to software engineering with agents, I split it into a few modes:

- Pairing: Me and one agent go at it together. I spend a lot of time reading every line it produces and reviewing its intermediate output. This is for one large chunk of work that needs my full focus.

- Orchestrating: I’m the conductor making many decisions at once. Anywhere from three to ten agents work on tasks of varying sizes. This is for highly parallelizable work.

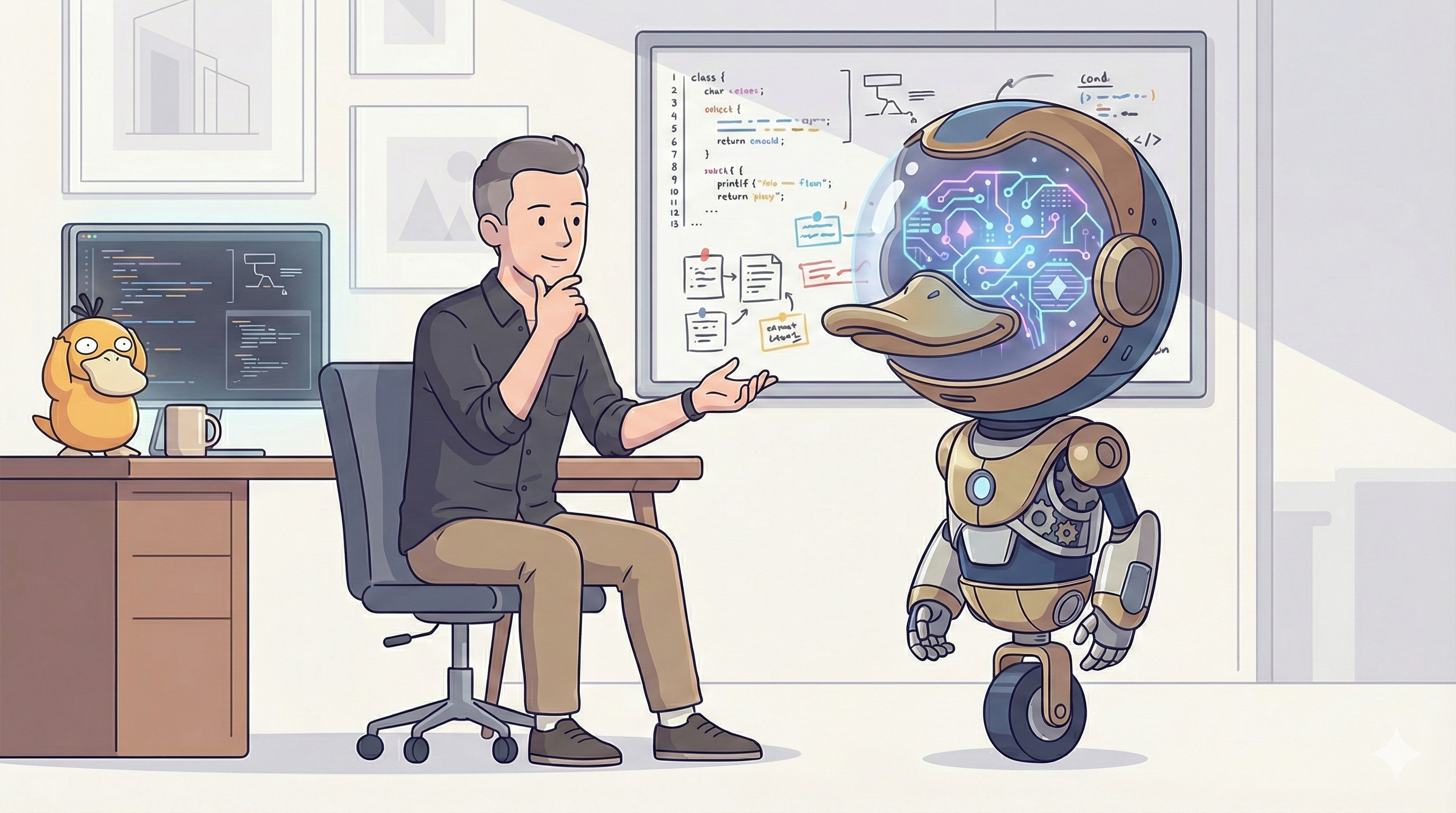

- Gizmoducking: Like rubber ducking, but with a much more intelligent duck. This is for planning, brainstorming, ideating, or building context in a new domain.

If you appreciate all of the references in the image above, give this post a ♥️

AI Driven Software Engineering

It feels like we have a new term for coding every month.

We moved from Prompt Engineering, to Vibe Coding, to Context Engineering, and who knows what’s next.

Previously, we had everything from coding, to programming, to software engineering, and everything in between.

At the end of the day, the goal is a product people love and are willing to pay for. Everything in between is just a means to an end.

That’s why I like to call it AI Driven Software Engineering.

I used to refer to this as LLM-enabled Software Engineering, but there is so much tooling and infrastructure around LLMs now that the term no longer does it justice.

Use TODOs to Move Fast TODO Everything

A little while ago I published a blog post titled Move Fast and Document Things.

This is a simple tool that enables engineers to stay focused without tending to side quests, while still getting the satisfaction of getting something off their mind:

- It doesn’t involve implementing the side quest

- It doesn’t involve creating an issue or a doc for it

- It doesn’t involve broadcasting it to everyone

- It simply involves adding a

TODO_<REASON>: <description>in the codebase

It makes sharing and picking up context easy. You get the dopamine relief of getting it out of your head. You leave breadcrumbs for other engineers and for future you.

This goes much further with agents.

Agents have full context of TODOs as they traverse a codebase, and you can even ask them to leave TODOs along the way for your next working session. More software teams need to adopt this pattern.

Make everything with Makefiles

Anyone who has ever worked with me knows how much I love Makefiles. Maybe too much, but it’s a hill I’m comfortable standing on.

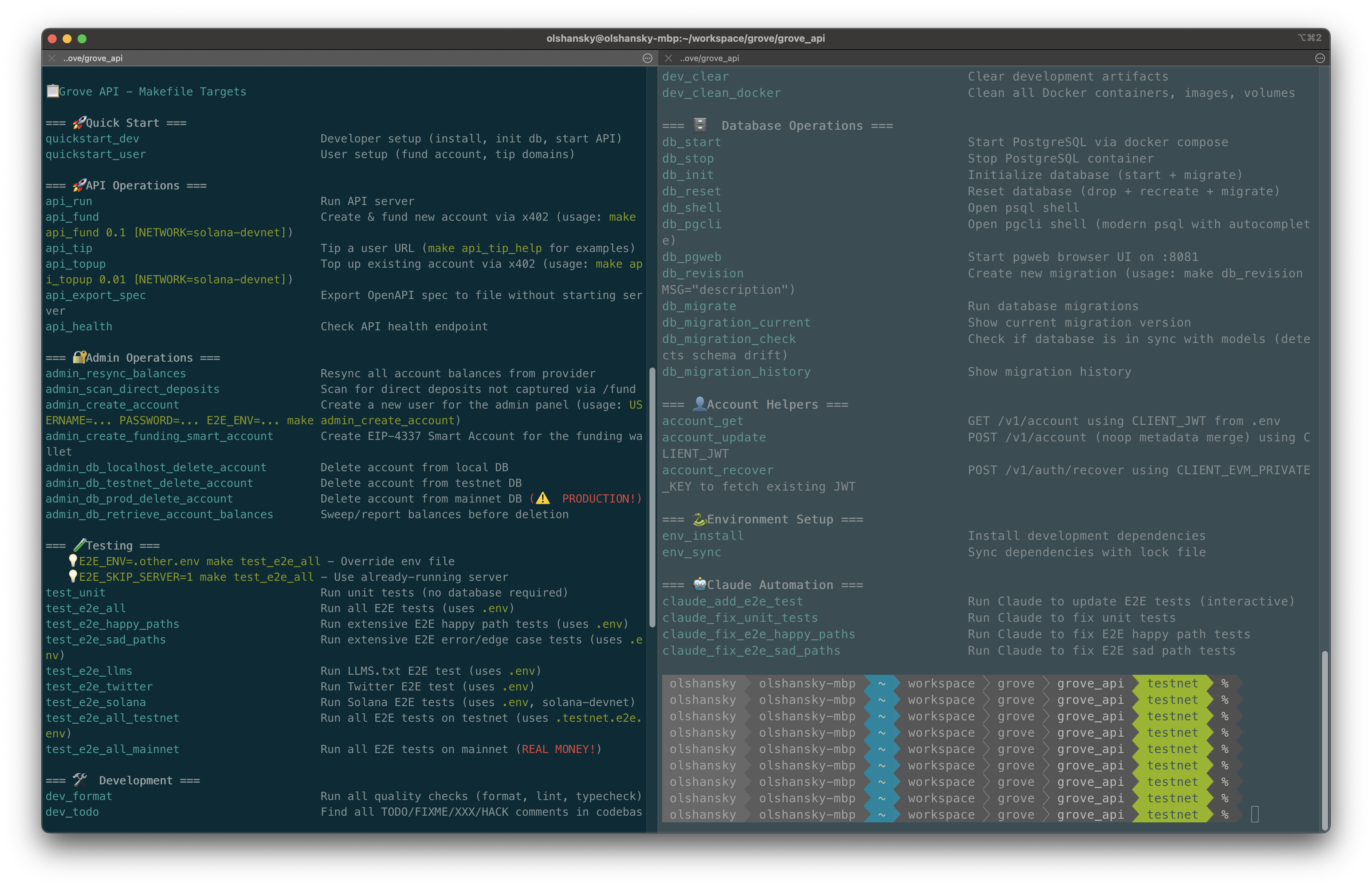

Personally, I see Makefiles as a universal CLI if configured correctly. In any repo I work in, the first thing I do after cloning is run make help to see all available commands:

This is more powerful than just helping humans.

- Quick onboarding: Instead of reading a README, anyone new to the codebase can run

make helpand get started immediately. - Agents: I can instruct agents to run specific make targets to build, test, and iterate until an end-to-end test passes. I can also ask them to create new targets so I don’t have to remember complex commands, flags, or environment variables.

- Smoke tests: I can reuse the same targets for end-to-end smoke tests in infrastructure, effectively killing two birds with one stone.

The agent angle is the part that feels under-discussed. Make targets become a stable interface between your intent and the messy reality of environments, dependencies, and “what do I run again?”

My bet is that Makefiles are going to make a comeback. Let’s see.

Skills Feedback Loop

I keep my Gemini, Claude, and Codex prompts and skills in a public prompts repo.

The only mature skill I have right now is for my Makefiles, with templates for different types of projects. I also have a handful of others that I use regularly. One of my favorites is code-review-prepare.

The most important piece: prompts and skills are not one-and-done, they’re something you maintain and evolve every day.

Documentation, scripts, tools, and best practices at any organization must be updated continuously. These are no different.

The only difference is that you can, and should, ask your agent to improve them at the end of every complex session.

You can either tell it how to improve the script in detail, or use the contents of your conversation as the direction. This is another pattern more software teams should start adopting.

Documentation

Anyone who has ever worked with me knows how much of a 🥙 I am when it comes to documentation.

I’m equally as much of a PITA (Pain In The Ass) when I review documentation from agents.

Nobody wants to read. Everybody just wants to copy-paste. 📠-🍝

Very simply, any documentation I ask AI to write involves:

- Short sentences or bullet points

- Copy-paste friendly commands

- Reduced cognitive overhead for both agents and humans

- No filler or fluff

- Start with a quickstart, only dive into “how” details at the end

- Bias toward section headers when possible

How will teams change?

This is a big topic deserving a post of its own, but I wanted to jot down a few quick thoughts.

The gap between product managers and software engineers will shrink. You won’t need product managers who cannot build prototypes, and you won’t need software engineers who do not have product taste. You’ll still need domain experts in both.

All engineering leaders and managers will be hands-on to varying degrees.

Best practices in engineering orgs will evolve from best practices about how to write code, to best practices about how to improve agents.

A handful of random pro tips

To keep this short, here’s a list of micro “pro tips” I use day to day:

- Planning: Ask the model to build a plan, then review it before execution.

- Take your time: Tell the model to spend at least X minutes on a task, and not come back until that amount of time has elapsed.

- Compounding: When you find a gap during a long back-and-forth, ask the agent to update its

agents.mdorclaude.md, or update or create a skill or slash command you can reuse. - Logging: Now that we don’t write much code, logs matter more. They are your window into what’s happening. I like long log lines with emojis, colors, and metadata. Agents are great at writing them.

- Don’t rush: For complex tasks, explicitly tell the agent to slow down and spend time thinking.

- Be idiomatic: Periodically ask agents what idiomatic patterns experienced teams use, and teach them your own conventions.

- Simplify: Ask agents to reduce branching, reduce the code’s surface area, and avoid over-engineering. A simple note here goes surprisingly far.

- Resuming: Every agent CLI has a

resumeoption to pick up conversations where you left off. Use it. - Yoloing: I bought a license to Arq backup and have embraced

--yolomode. - Ask for feedback: Give the agent permission to tell you what you’re missing. Ask it:

tell me why I'm wrongorwhat am I overlooking.

My favorite blogs

- Simon Willison: Founder of Django and a leading independent researcher on AI. He coined things like The Lethal Trifecta for AI Agents, Prompt Injection, the Pelican on a Bicycle LLM benchmark, and more. He’s been blogging for decades and you should support him if you read his work.

- Will Larson: A CTO who leads, codes, and reflects on strategy. Great content, but dense.

- xuanwo: An open source enthusiast who gets straight to the point without fluff.

- cra.mr: Founder of Sentry with a real, practical take.

- Boris Cherny: Creator of Claude Code. Enough said.

- Andrej Karpathy: One of the clearest voices on how LLMs work. Founder @EurekaLabsAI, ex-Director of AI at Tesla, co-founder at OpenAI. If you’re reading this and don’t know who he is, I genuinely don’t know how that happens.

Closing Thoughts

The meta point here is simple: the bottleneck is shifting.

It used to be “can you write code.” Then it became “can you design systems and lead teams.” Now it’s increasingly “can you translate intent into good work, repeatedly, through agents, without letting the codebase collapse into spaghetti.”

If you can do that well, you ship faster. You keep quality high. You keep taste in the loop. You also stay dangerously hands-on as a leader, which is going to matter more than people want to admit.

This post is mostly a reference for future me. If it helped you, steal the parts that work and ignore the rest.

Personal Followups

These are a few of my personal TODOs to go through after the holidays:

- Boris Cherny’s thread on X on how to use Claude Code

- https://xuanwo.io/2025/09-2025-review/

- Play around with orchestration tools like conductor to spawn multiple agents at once

- The “definitive” guide on how to use Claude Code

- Think through ways of how to make

CLAUDE.mdbetter in shared codebases - Think through ways of how to do less copy-pasting of large chunks of text

- Spend a bit of time on hotkeys (switching plan mode on/off), since it’s useful but I don’t have the muscle memory yet